A Glass Act

Posted September 1, 2021

Written by Heather Roberts, Research Historian

For a printable version of this article, please click here.

Did you know…

Next time you’re at Rosson House, take a look at the windows – the one just to the left of the front door is easiest to get close to – and you’ll likely notice that the window isn’t perfectly smooth or free of imperfections. That means the window you’re looking at is original to the time when Rosson House was built, over 125 years ago. Some of the windows (including several of the interior transom windows and the large, beveled-edge plate glass window in the front of the house) are actually original to the home, and others were replaced with period-accurate windows during restoration, taking them from other turn-of-the-century buildings that were being torn down as Rosson House was being saved.

A 7th century stained glass window from St. Paul’s Monastery in Jarrow, England. Photo by Aidan McRae Thomson, 2019.

Before glass windows were readily available and affordable, windows were made of many things, including parchment, oilcloth, mica, or thin sheets of animal horn or animal skins. Sometimes they were simply window frames without anything in them, but with shutters to close against the elements or for security. Glassmaking in general is believed to have originated around 4,000 years ago in Mesopotamia. Glass was first used in windows – little more than small pieces of partially translucent glass set into walls – around 2,000 years ago in Roman bathhouses. As early as the 7th century CE, churches and monasteries in Europe were installing windows made of pieces of thick, flat, colored glass held together with iron and lead framework, like the antique square-shaped one you see here (which honestly reminds this author of something you might find in a Frank Lloyd Wright home…).

-

Seeing Red

It wasn’t until the 16th century that glass windows became common in ordinary homes. Windows panes were created by blowing glass into a cylindrical shape, and then cutting the still-malleable glass into smaller pieces, or blowing it into a sphere that would be flattened into a glass disk, like in the window pictured at the top of the page. The windows themselves would then be made of these smaller, albeit thick pieces held together with metal framework. Glass windows like these were available in Colonial America, but if you wanted any kind of glass – mostly windows and bottles at this time – it had to be shipped across the Atlantic on a months-long trip. The first glasshouse in America was built in Jamestown, VA in 1608, but scholars don’t think it stayed in business more than a couple of years. Though others tried and may have been successful on a smaller scale, it wasn’t until Caspar Wistar founded the United Glass Company in Alloway, NJ in 1739 that a large-scale glasshouse was successfully established in America.

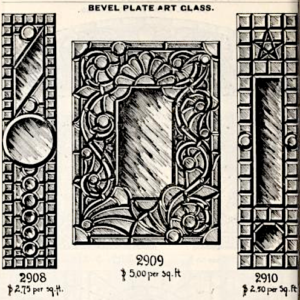

Like the early American immigrants, people who lived in the Arizona Territory had to have materials like glass windows shipped to them. Instead of months, though, it would take about a week to have a window sent from J. D. Hicks & Company (Los Angeles) to Tucson on a stagecoach. They (and others) advertised in Arizona newspapers as early as 1866, selling everything from broomwire to windows. When the railroad finally came to town, it changed shipping to take a mere fraction of that time. The Rossons likely had their windows sent from San Francisco and/or Chicago, whether through local hardware stores or via mail-order (their architect, A.P. Petit, was originally from the former, but many mail-order catalogs were headquartered in the latter). We know the Rossons ordered their door hardware from the Hibbard, Spencer, Bartlett & Co. catalog (c1891, based in Chicago), and that windows were available for purchase from the catalog as well.

Like the early American immigrants, people who lived in the Arizona Territory had to have materials like glass windows shipped to them. Instead of months, though, it would take about a week to have a window sent from J. D. Hicks & Company (Los Angeles) to Tucson on a stagecoach. They (and others) advertised in Arizona newspapers as early as 1866, selling everything from broomwire to windows. When the railroad finally came to town, it changed shipping to take a mere fraction of that time. The Rossons likely had their windows sent from San Francisco and/or Chicago, whether through local hardware stores or via mail-order (their architect, A.P. Petit, was originally from the former, but many mail-order catalogs were headquartered in the latter). We know the Rossons ordered their door hardware from the Hibbard, Spencer, Bartlett & Co. catalog (c1891, based in Chicago), and that windows were available for purchase from the catalog as well.

-

In a Glass by Itself

How expensive a window was depended on how big or how elaborate it was. For instance, something as big as the picture window at the front of Rosson House, though it only has a simple beveled edge, would have been very expensive. The largest readily available windows we’ve been able to find in period catalogs (so far) are 40”x60”. The Rosson House picture window is about 72”x96” – definitely a custom order – and the shipping likely cost more than the window did itself. The expense of these kinds of windows created a demand for insurance based on protecting those purchases – the 1898 Phoenix City Directory listed the Frankfort Accident & Plate Glass Insurance Co., and the New York Plate Glass Insurance Co. We don’t know if the windows at Rosson House were insured when it was first built, but they definitely are now!

Information for this blog article was found all over the Corning Museum of Glass website, including The Origins of Glassmaking and About Medieval Glass, but probably many other places there as well; The Met and My Modern Met websites; National Park Service Historic Jamestown website; Engines of our Ingenuity; Historynet; the History of Stained Glass; the Hibbard, Spencer, Bartlett & Co. catalog c1891; the Foster Munger Co. Catalog, c1895; and the Library of Congress Chronicling America digital newspaper archive.

Archive

-

2025

-

2024

-

2023

-

2022

-

2021

-

2020

-

2019

-

2018

-

2017

-

2016

-

2015

-

2014